Bulgaria votes – Again!

At the end of this week, the Central Election Commission will formally confirm the names of Bulgaria’s new MPs and next week, President Rumen Radev will announce the date on which he will convene the new parliament’s first session. There is little festivity in the parties’ headquarters and among voters because the October 2 elections – the fourth in just a year and a half – did not produce a clear majority that would contribute to forming a stable government.

This continued political crisis started following the popular anti-corruption protests in 2020 that led to ousting of the centre-right government of Boyko Borissov, the veteran leader of the Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB), who had been in power for over a decade. Two “new faces”, Kiril Petkov and Asen Vassilev, challenged the status quo and formed We Continue the Change (WCC), a centre- and left-leaning new movement, which came into power in November 2021 in a four-party coalition format including Democratic Bulgaria (DB) – centre and right-leaning, the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) – left, and There Is Such a People (TSP) – a populist, anti-system movement, formed by popular TV star Slavi Trifonov. The four partners’ common goal was to dismantle Borissov’s “corrupt model” of governance. Just seven months after coming into power, in June 2022, the government lost a no-confidence vote in parliament after one of the partners, TSP, left the coalition, blaming WCC for corrupt practices. Since then, a caretaker government appointed by President Rumen Radev has led the country.

Are There Any Winners?

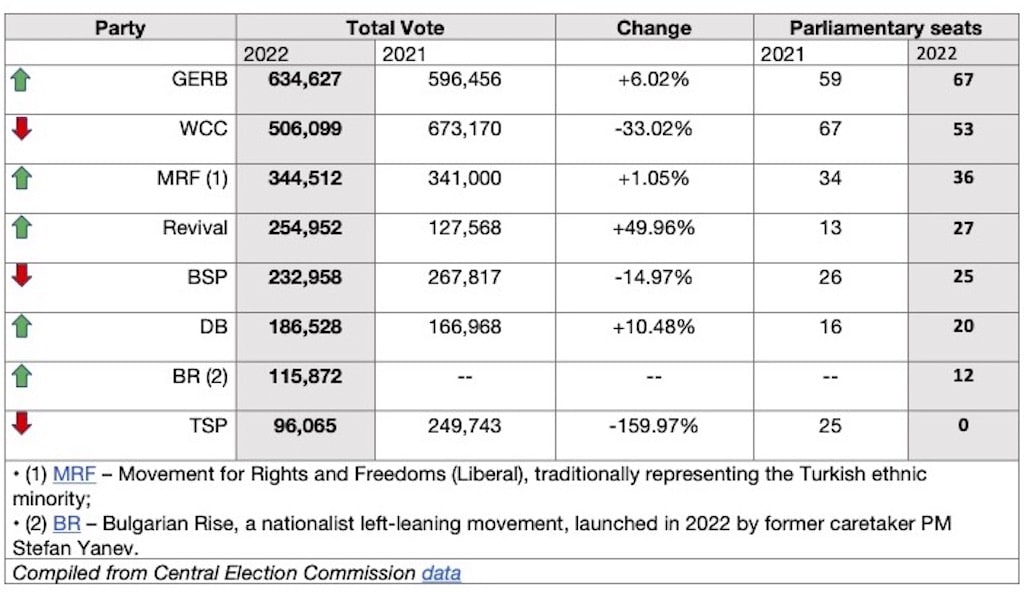

The October 2 elections saw the return of GERB as it won the most seats; a significant decrease in the “protest” parties’ support; the doubling of the size of the ultranationalist Revival; as well as the decline of the TSP, which from being a leading party in 2021 now dropped to below the four % threshold needed to enter parliament.

As a result of this election, the "pro-change" movements now have fewer seats than the "status quo" parties. Even if the formal winners are Borissov and GERB, in fact, all contenders are losing in one way or another. The new parliament’s configuration and the distribution of seats between the seven winning entities do not give much hope for forming a stable government – a priority of voters, according to a recent poll. As sociologist Boryana Dimitrova noted in a TV interview, the desired coalitions are impossible, and the possible ones are unacceptable.

The key players aren’t willing or able to take the political responsibility for forming a government, which would require compromising and making major concessions. GERB’s legitimacy regarding corruption complicated Borissov’s chances to find allies among the other parties, most of which ran on an anti-GERB platform that would make uniting with GERB “treason” in their voters’ eyes. On the other hand, unlike in the previous parliamentary configuration, the prospect of forming a coalition without GERB is questionable. Some observers believe that the new parliament will ultimately be able to form a government since the parties will use the urgency of a cold winter with high prices as an excuse for changing their stances and warming up with GERB. For others, the post-election mood suggests that the more likely scenario is for the political instability to continue and for a new snap election to occur in the spring of 2023.

Regardless of how the situation develops, President Rumen Radev’s role will further increase in the period until a government is formed. Re-elected in 2021 for a second 5-year term, Radev is the most approved and trusted political figure.

Caretaker Government

After the new parliament is constituted, the president will hand an exploratory mandate for forming a government to the largest political bloc. If their attempt fails, the mandate will go to the second largest group, and if a third mandate is to be issued, it will go to a party of the president’s choice. If no party succeeds in forming a government, the president will call, once again, early elections. A new caretaker government will assume the executive power with an average lifespan of about three months until an election is held. If this happens, it will be Bulgaria’s ninth caretaker government in recent history and the fifth formed by President Radev.

Radev said that he will allow sufficient time for dialogue between the parties in line with the procedure and called for the parties to take responsibility, engage in dialogue, and demonstrate “understanding and wisdom” instead of drawing red lines.

In Bulgaria, caretaker governments are appointed by the president. They have limited powers, and their main task is to organise fair elections during periods when no parliament is in session. Typically, the ministers are non-partisan, and they enjoy high public approval. Initially meant to ensure impartiality and balance in between legitimate governments, the caretaker governments are increasingly seen as becoming an instrument that the president, who constitutionally has no role in the executive and the legislative powers, can use to impose his own political agenda. In addition, another caretaker government would further undermine confidence in parliamentary democracy and strengthen the sentiments for “a strong hand” and “a presidential republic”. Radev’s critics claim that, through the caretaker government, he will keep the country less engaged with supporting Ukraine and “reproduce pro-Putin messages”.

Options for a New Government

Effectively addressing citizens’ priority issues such as high prices, inflation and energy supplies, as well as strategic decisions related to the state budget, the Eurozone, the Schengen space and the Ukraine war would require a regular government with full powers and political responsibility, along with a functioning parliament. There are hardly any winning moves with regard to forming a majority. A “classical” coalition with either a few political partners or a grand alliance would be challenging to form. Alternatively, the option of an “expert” government, as opposed to one clearly dominated by parties, is not seen as positive because of Bulgaria’s bitter past experience with expert governments such as Oresharski's (2013-2014) and Berov's (1992-1994), in which shadowy business interests actually pulled the strings. The option of a minority government would, too, be unlikely to survive in the current polarised political environment that lacks the culture of compromise.

GERB’s leader Boyko Borissov took the initiative by calling on all leaders to step back and give priority to non-partisan figures for forming “a Euro-Atlantic parliamentary majority and government” and suggested forming a contact group to facilitate the negotiations: a format successfully used in Bulgaria in the 1990s. Reputable individuals such as President Rosen Plevneliev (2012-2017) and former foreign minister Solomon Passy (2001-2005) agreed to lead the contact group, which is due to be formed after the parliament convenes. Plevneliev extended an invitation to “all pro-European and pro-democracy entities” elected in parliament to discuss the priorities of a future cabinet. So far, both We Continue the Change and Democratic Bulgaria have declined the invitation: they see the collaboration with GERB as “toxic” and harmful to their political legitimacy. The outcomes of the contact group initiative would demonstrate to what extent GERB has overcome its political isolation and stigmatisation by its competitors.

The Election Campaign

The election campaign lacked energy and enthusiasm and was abundant with negative and radical messaging, questioning the opponents’ legitimacy and competency. Unlike the previous election campaign, in which GERB was the status quo, and WCC was the change, now the two main players have repositioned themselves. Personal attacks dominated the conversation over ideas, visions, and principles. The parties fuelled divisions and avoided the constructive debate about policies – too many red lines were drawn, which the parties now struggle to cross and collaborate in a coalition. Most parties focused entirely on mobilising their core electorates and did little to engage the periphery. The voter turnout, 39.4%, was low, mirroring the last few election cycles, while the voters who chose the "I do not support anyone" option doubled in number. Exit poll data show that the share of youth voters has decreased from 18 to 14%.

With a well-organised, visible campaign, prioritising direct meetings with voters across the country and face-to-face interactions with candidates and leaders, GERB fully mobilised its core support and increased its last election’s score by 38,000 votes, or 6%. One reason for that is the fact that GERB is traditionally strong on the local level – a priority that its leadership has pursued for a decade. The campaign projected images of halls full of supporters coming to meet the candidates all over the country. Their messaging sought to prove that former PM Kiril Petkov’s government was incompetent and dangerous and that, with GERB, voters would get predictability and stability after more than a year in opposition. However, like most other parties, GERB struggled to attract its peripheral electorate.

We Continue the Change’s campaign targeted three main audiences – those who care about the fight against corruption, the youth, and the retired – talking about their achievements in dismantling GERB’s corrupt practices and raising pensions while avoiding taking a stance on major international themes such as the Russian war in Ukraine. Often, TV coverage of campaign events showed empty halls with very few supporters engaging with their candidates – not necessarily because of the lack of supporters, but perhaps due to poor organisation.

WCC’s narrative against GERB was quite aggressive and radical, while WCC’s opponents, the media, and even the president did not miss any opportunity during the campaign to criticise and discredit their lack of experience and failures in government. Part of the anti-WCC narrative included that it is “an engineered political project” whose ratings are undeservedly high and will ultimately fade away. In this election, WCC lost one-third of their November 2021 electorate, or 167,000 votes. As with most new movements, WCC’s voters are quite volatile – the party had the highest level of dispersing original supporters compared to the other entities. If the trend of alienating supporters continues and a new snap election takes place next spring, WCC could face challenges similar to those of TSP who could not pass the four % threshold to enter parliament. Now that the 2022 elections are over, WCC – which recently got its official registration as a political party – should urgently prioritise creating and strengthening a partisan infrastructure horizontally and vertically, and – importantly – cultivate cohesion and common values.

MRF came third with a solid result, slightly higher than in the last election and, as usual, managed to consolidate its very disciplined electorate. MRF’s messaging was about professionalism and highlighting the party’s experience in governance as a way to curb any association with corruption and clientelism. Following the election, MRF’s leader Karadayi called on all political leaders to overcome their egos and seek unity, stressing that MRF would enter into coalition with all parties willing to take the responsibility.

Revival’s result doubled in comparison to 2021, but it seems that the party has reached its peak. It mobilised the radicalised voters with its anti-EU and pro-Kremlin rhetoric and secured 10% of the seats in parliament – less than in other European countries. However, it will be difficult for Revival to translate its result into participating in government because all the other players distance themselves from extremism. If "Revival" chooses to back a potential coalition government, it risks losing much of its support, repeating the fate of “Ataka” – due to its participation in government, “Ataka” dropped from 258,481 votes in 2013 to 7,605 votes in 2014.

BSP, Bulgaria's oldest party, experienced a loss of 15%, or 34,000 votes, compared to the November 2021 elections. Part of its electorate was attracted by WCC's social messages; others chose “Revival” for its anti-Western rhetoric; while others chose the pro-Russian “Bulgarian Rise”. During the campaign, the party emphasised its successes in social policy as part of the government and, at the same time, criticised the foreign policy positions of its coalition partners, particularly the firm stances they took against Russia. Inside the BSP, which participated in Petkov’s government, voices are calling to solve the party’s leadership issues and to focus on its overall ideological direction to curb the trend of continued loss of support.

DB got approximately 20,000 more votes than in November 2021 and came sixth in the new parliament. Its campaign focused on its traditional supporters, who are people in the big cities with high-end professions, and attempted to also reach out to more “mass” voters in smaller towns and rural areas. A key message was that DB brings wisdom and expertise and that this election is “the struggle of the ages” where a choice has to be made: going to the future or staying in the past.

Bulgarian Rise, led by former caretaker PM Stefan Yanev, crossed the barrier to enter the parliament probably because its leader was seen as being close to President Rumen Radev. Yanev then became minister of defence in Kiril Petkov’s government but was removed because of his pro-Putin positions. A solid portion of BR’s votes came from WCC according to exit polls. Following the elections, Yanev announced that “Bulgarian Rise” is willing to participate in a coalition.

“There is such a people”, in just 11 months, has melted its result by 160%, or almost 154,000 votes, and didn’t pass the threshold to enter parliament. As in previous elections, the party relied entirely on online voter mobilisation and communication with citizens. According to TSP’s critics, the movement’s destructive role in three consecutive short-lived parliaments contributed to discrediting the parliamentary system.

Yet Another Snap Election?

If the parties are unable to form a government and a new election is called for the spring of 2023, the question would be if the emergence of the WCC movement in 2021 has really contributed to “refreshing” Bulgaria’s political system, bringing new perspectives, and better responding to voters’ aspirations; or has had a negative impact, keeping Bulgaria in a state of permanent political crisis, growing polarisation, stagnation, and the inability to form functioning governing coalitions.